- Home

- Margaret J. Anderson

Searching for Shona Page 4

Searching for Shona Read online

Page 4

Chapter 4

Clairmont House

The next few weeks were a strange and troubling time for Marjorie. It wasn’t so much the fear of being found out that worried her now so much as the ease with which she was accepted as Shona. One day in October she was issued with a blue identity card, made out to Shona McInnes, and later a ration book. Sometimes she thought that even if she told the Miss Campbells or Miss Dunlop that she was really Marjorie Malcolm-Scott, they wouldn’t believe her. After all, hadn’t the Government issued her with a special identity card saying she was now Shona McInnes, number SOCC-6-3? To Marjorie that card and number made the rash change in Waverley Station terribly official and complete.

But at the same time she was troubled by the fact that she hadn’t really become Shona McInnes at all. She had Shona’s name, her clothes, and her painting hidden under the bed, but she was still the lonely, rather uncertain Marjorie Malcolm-Scott. She knew that. Anna would say, at least once a day, “Shona didn’t do that,” or “Shona would have done this.” And since the German spy episode on the first day of school, Marjorie had been uncomfortable with the Canonbie children. She was a long way from being the bold, self-confident leader that Shona was.

However, Marjorie was not unhappy. She enjoyed living with the Miss Campbells. Miss Morag was bossy and Miss Agnes was fussy, but underneath they were both kindly souls. They provided the girls with a few much-needed clothes from their shop and taught them to knit so they could make khaki scarves and squares for blankets for the soldiers. Like Mrs. Kilpatrick, the Miss Campbells were very conscious of the War Effort. Anna and Marjorie were their War Effort.

They expected Marjorie to help around the house, and she liked that. Mrs. Kilpatrick had always complained that she was in the way when she did anything in the kitchen.

“It’s time you learned to cook,” Miss Morag said one day, getting out a big, well-worn recipe book. “We’ll start with scones. I don’t suppose they let you do any cooking in the orphanage.”

“No, they didn’t,” Marjorie said “Cook was always too busy to have us underfoot.”

Marjorie had somehow managed to fuse the experiences of her own past life with Mrs. Kilpatrick and pieces of information she’d learned about the orphanage so that she answered Miss Campbell’s questions without hesitation. At first she felt a little guilty talking about St. Anne’s, but now it was almost as if she had lived there.

Marjorie weighed out the flour and lard for the scones and measured the milk under Miss Morag’s watchful eye. She let Anna mix the ingredients and cut the round scones into segments.

Anna would have liked to learn to cook as well, but she couldn’t read the recipe book. Even the numbers on the scale they used for weighing the ingredients confused her. Anna was nine, but she had been put back to Primary One at school because of her reading. “The baby class,” she called it angrily. She had trouble with writing, too. She kept getting the letters backwards. Marjorie had noticed that Anna’s printing often came out like mirror writing, and she thought it rather clever, but Anna’s teacher wasn’t impressed. She scolded Anna, telling her to start over again, and Anna became more and more discouraged.

Marjorie, on the other hand, was doing fine at school. In March all the children in the top class would sit the Qualifying Exam, and Marjorie knew that Miss Dunlop expected her to do well in the exam—well enough to be selected to go to Nettleton Academy the following year. But Marjorie didn’t really believe she would still be in Canonbie the following year. The war would be over long before then, she told herself, and she and Shona would—somehow—have changed back.

The idea that the war wouldn’t last long was strengthened by the fact that when she arrived at school one Monday morning both Jimmy Davidson and Douglas Craik’s desks were empty. Because there had been no air raids, they’d gone back to Edinburgh, along with many of the other evacuee children.

School was much better for Marjorie without Douglas Craik and his teasing and bullying, but she wished she had friends in her class. The thought of all the friends Shona would have made nagged at her. She was always with Anna at playtime and lunchtime, and the other children often referred to her and Anna as “them evacuees.”

One afternoon, early in December, Marjorie was helping Anna with her reading. They were alone in the house because both Miss Campbells were still at the shop.

“Tommy was Spot,” Anna read haltingly.

“Think about what you read,” Marjorie said,

“Tommy saw Spot,” Anna corrected herself, and continued to read. With Marjorie’s help, she got all the way through the book. Then Marjorie looked at the clock and saw that it was time to start making supper. Anna set the table.

Soon the kettle was boiling and everything was ready. Marjorie went around the table changing the places of the knives and forks. Poor Anna always got them mixed up.

“I like you better than Shona,” Anna said suddenly.

”Why?” Marjorie asked, quite taken aback.

“You don’t shout so much when I get muddled. And you don’t get me in trouble like Shona did.”

“Did Shona get you in trouble?” Marjorie asked, quite eager to hear Shona criticized. Mostly Anna talked about how brave Shona was and the exciting things she and Shona had done together.

“Once she put salt in the sugar bowl for a joke, and when Matron got salt in her tea she was angry. Shona said I did it, and Matron believed her.”

“That wasn’t fair,” said Marjorie. Anna made enough mistakes without taking the blame for other people’s tricks.

Then the Miss Campbells came in, their round glasses misted over with rain. They hung their tweed coats and green headscarves near the fire to dry off and propped their umbrellas in the bathtub.

“It’s good to come home to the kettle boiling and the table nicely set,” Morag said. “We’ll have a boiled egg with our tea and some of Agnes’ plum jam on our bread.”

She switched on the wireless, and Marjorie and Anna were obliged to be quiet while everyone listened to the news. Marjorie hated listening to the news. She preferred not to think about the war at all, but that was hard when the Miss Campbells talked about it so much, and never, never missed the six o’clock news.

Later that evening Marjorie and Anna began to make plans for Christmas. This posed quite a problem because neither of them had any money, and they were both anxious to give the Miss Campbells presents.

“You could draw them a picture,” Anna suggested. “That’s what Shona gave Matron last year. She drew a picture of a horse—ever so nice, it was.”

“It wouldn’t be nice if I drew it,” Marjorie said sharply. “I’m not Shona, you know.”

For a moment, Marjorie considered giving them the picture from under the bed, and then decided it wouldn’t be fair.

“Maybe we could earn some money,” suggested Anna.

“Miss Dunlop sometimes gives a penny to the first one to get the right answer in mental arithmetic,” Marjorie said. “I’m sure I could get some money that way.”

”But I couldn’t,” Anna said rather sadly.

The following Saturday, Agnes Campbell gave each of the girls a shilling, saying they could spend the afternoon at the cinema and buy themselves chips on the way home.

“Let’s not go,” Marjorie whispered. “We’ll save the money for presents. Two shillings would be a good start.”

“What will we do instead,” Anna asked. She, more than Marjorie, hated to miss going to the pictures.

“We’ll go for a walk. We’ll go down the hill away from the town and find out where the road leads.”

As soon as they had finished lunch, the two girls put on their coats, hats, and gloves and set off down the road. It would have been much nicer to spend the afternoon in the dark warmth of the picture house than to go for a lonely walk in the country on that bleak December day, but the girls plodded on. They passed the last houses of Canonbie, and then the road became narrower, and on either side of them w

ere empty fields. The skeletons of last year’s roadside flowers stood out against the leafless hedges, and a field, recently ploughed, lay dark and empty.

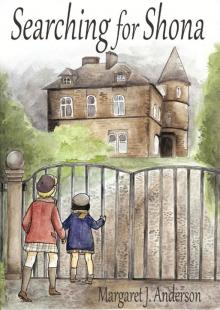

Then they came to one more house, bigger than any of the other houses they had passed. They could only see parts of the roof as they approached it, because it was mostly hidden by tall trees and a high wall that surrounded the whole garden. On the gatepost, in fancy lettering, was the name, “Clairmont House.” Then, seeing the house clearly between the bars of the iron gate, they gasped in surprise.

“It’s Shona’s house,” whispered Anna.

“It does look like it,” Marjorie agreed, though there was something about it that was not like the house in the picture.

“It’s pretty,” Anna said.

That was it, Marjorie realized. The house was pretty—not sad and neglected as it was in the picture. The great stone balls rested on top of the square gateposts where they belonged. The gates were tightly shut, not hanging half open, bent and rusted. And although the garden was untidy, as most December gardens are, it was not wild and neglected. The house looked empty. The downstairs windows were shuttered, and there were no curtains on the upstairs windows.

“Can we go in?” Anna asked.

“No, of course not,” Marjorie answered.

“Shona said she would take me to her house,” persisted Anna. “She said I could meet her family.”

“We can’t go in,” said Marjorie. “Besides, there’s no one there. You can see that the house is closed up and empty.”

“Shona said I could see her house,” Anna whined.

She leaned against the gate pushing her small face between the bars to get a better view of the house. The gate swung noiselessly open, and Anna, without a thought, slipped inside. Marjorie hesitated for a moment and then followed Anna up the driveway.

Chapter 5

The Turret Room

Marjorie and Anna walked up the long driveway, the gravel crunching under their feet. On one side was a dense shrubbery of dripping rhododendron and laurel bushes, and on the other a smooth lawn, sloping down to a border of trees and shrubs. The driveway divided, and they hesitated for a moment, wondering whether to approach the front or go around the back. They decided to follow the sweep of the driveway to the front door and climbed the flight of shallow steps.

It was an imposing door. The sort of door you’d expect to be flung open by a stiff, uniformed butler. Anna reached for the big, brass doorbell, but Marjorie stopped her.

“Suppose someone comes,” Marjorie said. “What will we say?”

“That we want to see Shona’s house,” Anna answered.

Marjorie was having trouble sorting out her thoughts. She was still overwhelmed by the strange coincidence of finding the house. Even though she had remembered Shona saying that her mother came from Canonbie and that the picture held a clue to her past, she had not believed that the house actually existed. Now, having found it, she felt she owed it to Shona to find out more. But suppose someone connected with this house did know about Shona, what would Marjorie do then? Should she go on pretending that she was Shona?

Meantime Anna, who only wanted to see inside Shona’s house, pulled the bell. On hearing the faint ringing echoing in some distant part of the house. Marjorie waited anxiously and was greatly relieved when there were no answering footsteps.

“Let’s go round to the back door,” Anna suggested.

Marjorie followed Anna around to the back with a little more confidence now that she was sure the house was empty. Behind the shrubbery was a walled kitchen garden, with leafless apple trees espaliered against the walls. A few brown, rotting apples still hung from their bare branches, and a greenhouse with broken panes and a sagging door added to the lonely, unkempt appearance of the winter garden.

But the garden didn’t interest them. They were drawn back to the house. They crossed a cobbled courtyard surrounded by low buildings. Anna tried some of the doors, but they were all locked.

“There are so many doors!” Anna said.

“I suppose these were stables in the olden days. And this must have been the washhouse,” Marjorie answered, looking though the cobweb and dust encrusted panes of the window. “I can see washtubs and an old copper boiler.”

They came to the back door of the main house and, bolder now, they tried to turn the doorknob. That door, too, was locked, as they had expected. Reluctant to leave, they peered in a window. They could tell from the big, black range that this was the kitchen, and they could see a heavy sideboard, the only piece of furniture in the room. Its partly open doors and bare shelves bare confirmed that no one lived in the house.

Then the rain, which had been threatening all afternoon, began to fall in big drops.

“We’re going to have to find some shelter,” Marjorie said, looking anxiously at the heavy clouds. “Maybe we should go over to the greenhouse.”

Anna was pushing on a little square door, quite low in the wall, and gave a sharp cry of excitement when it swung open, leaving a gaping, black hole. Marjorie stooped down and stuck her head inside, breathing in stale, sooty air.

“It’s the coal cellar,” she said. “It’s like my house in Edinburgh. The coalman dumps the coal in here, and the maid reaches it from a door in the house. That way she doesn’t have to go outside to get coal for the fires.”

“Can we go in?” Anna asked.

“Of course not,” Marjorie said firmly. “We can’t go creeping into someone else’s house.”

There were times when Anna could be very stubborn and single-minded, and this proved to be one of them. Ignoring Marjorie’s protests, she dropped down inside the coal cellar and quickly disappeared into the sooty darkness. Marjorie could hear the crunching sound of Anna’s feet as she stumbled over small pieces of coal scattered on the floor. Then came the triumphant shout, “It’s not locked! We can get in!”

Anna opened a door, letting a shaft of light shine down into the cellar, and then she stepped into a hallway.

“Hey! Wait for me!” Marjorie shouted. She couldn’t let Anna go inside alone. Besides, she had to find out more about the house—she owed that to Shona.

The door through which Anna disappeared led into a small back hall with several doors opening off it. One looked like the back door and was firmly bolted. Anna was not in any of the back rooms. Marjorie finally found her standing in the main hall, gazing up at the curve of the staircase and a crystal chandelier hanging from the ceiling, high above her. Light filtered down from the upstairs landing windows. They tiptoed forward and opened a door into one of the front rooms. A damp, musty smell greeted them. The windows were tightly shuttered, so that all they could see was the faint shapes of a few articles of furniture draped in dust cloths. The other downstairs rooms were also dark and empty.

“I want to go upstairs!” Anna said.

“We’d better go back outside,” Marjorie answered uneasily. She could hear faint creakings and other unexplained noises as they stood together in the hall. Suppose someone came in and found them there.

“I’m going to see the bedrooms,” Anna said, and walked boldly up the big staircase.

Anna’s persistence reminded Marjorie of the day she had taken Shona through the house on Willowbrae Road. Both houses belonged to the same Victorian era, but here the uncarpeted stairs and lack of furniture made the house and all the rooms seem unnaturally big, as if they had entered the oversize home of some great, sleeping giant. The bedrooms, too, were unfurnished, except for the occasional chest of drawers or wardrobe. Marjorie gave a start of fright when she walked into the marble bathroom and caught sight of her own reflection in the mirror. The bathtub, which like everything else, seemed giant size, stood high off the floor on great clawed feet.

At the back of the upstairs landing was another staircase. Marjorie guessed that, like the back stairs in her own house, this would lead from the servant’s attic bedrooms on the third floor directly down to the kitchen quarters.

“Come on

up!” Anna said. She was obviously enjoying exploring the empty house.

“These would be the maid’s rooms,” Marjorie said, looking into one of the small, narrow rooms under the roof. She was trying to imagine which part of the house Shona was connected with. Had her mother, perhaps, been a servant here, sleeping in one of these little rooms, or had she belonged in the big, oversize front rooms? Somehow the emptiness and echoing stillness of all the rooms made it hard to imagine the people who had lived here. There were no clues at all to tell who they were.

“Can we go into the big bedrooms again?” Anna asked when they went back down to the landing. She opened a door that they hadn’t tried before and shouted, “There are more stairs behind this door! Come on!”

Even Marjorie forgot her uneasiness when she saw the narrow spiral staircase. It must wind up inside the turret they’d seen from the outside. When Anna reached another door at the top of the stairs, she gave a gasp of delight as she pushed it open and stepped into the tower room.

It was a little room, almost circular, and unlike the other rooms, this one was completely furnished. A window seat with dark red velvet cushions followed the curved contour of the wall. The windows above it reached almost to the ceiling, so that in spite of the heavy skies and beating rain the room seemed bright. The curtains were velvet, and the floor was covered with a richly patterned carpet. A couch with carved wooden arms and dark blue upholstery angled across in front of a small fireplace, tiled with blue and white Dutch tiles. On the mantelpiece above it were two stiff toy soldiers standing beside sentry boxes. There were dead ashes in the fireplace, as if the fire had only just gone out.

A child’s desk and a small chair stood near the door. Against the opposite wall was a cupboard with doors slightly ajar revealing worn books and old toys. A high, narrow pram with a canopy and a rocking cradle were arranged beside the cupboard, and there was also a small table set for tea.

Searching for Shona

Searching for Shona The Journey of the Shadow Bairns

The Journey of the Shadow Bairns